A sorte e o risco, emoções fortes

Whether it's luck or misfortune, only time will tell.

This phrase is part of a traditional tale that was once set to music by Pé na Terra, a folk/traditional music band, and told and adapted by Ana Lage. It tells the story of a boy, his dream of having a horse and the various events that occur in his life to achieve this goal. Some positive, some negative, but with the certainty that chance is a constant and time is our ally on this journey in search of goals.

The future is unknown. After a certain result obtained, we can be left with the feeling that it was luck or with the excuse that it was bad luck. One of the main functions of an investment plan is precisely to limit the effect of luck or misfortune and even the risk itself, controlling it and converting it into positive results over time. Basically, avoid letting emotions control the decision-making process. This tale alerts us to precisely that, that we cannot be dependent on luck or misfortune, but rather on time, patience and optimism about the future. This is investor wisdom.

For those who have invested consistently, patiently and confidently in the future, the last few decades have brought spectacular success and returns. But it wasn't linear. We've had recessions, bankruptcies, wars, bubbles, and even a kind of capitulation in the market. That is, many investors failed to obtain the desired results. Why did they make the wrong decisions? Why did they get carried away by emotions? By luck or bad luck? Because they took too much risk?

Our view is that investing in the financial markets should not be seen as a game or as speculative moments. Here we explain the difference between an investor and a speculator. They are both important for the financial markets, but it is not the role of the speculator that we are defending here. It is also not a test of faith, that everything will be fine and luck will be on our side.

Along with History

History does not repeat itself, but we do (Voltaire: “History never repeats itself, but man always does”). We are constantly making the same mistakes and making the same decisions. We like routines and are comfortable with the idea of control. This control is often looking at a monitor and watching the price changes of a particular asset. Are we really in control or just taking up our precious time?

In this context, looking at history is important, as it becomes an alert to the consequences of decision-making. The results may even be different considering the moment, the conjuncture, but it comforts us to understand what happened in the face of a given problem.

But the problem will be different. We are different. The world has also changed. History tells us that. That each case is a case, and what was good then may not be good now. If we believe this, that history repeats itself, we are putting an extra dose of luck and risk into the investment process. In addition, the results do not depend only on us.

Morgan Housel, in The Psychology of Money, writes that luck and risk are brothers. Basically, it means that much of what happens in our lives, and in investments as well, is the result of these 2 brothers.

That's why it becomes so difficult to get good and immediate results from books like: What are the best investment strategies? How to get rich? How to win in the stock market? Not because they are bad books or bad advice. It's not that. It is because those lessons, those advices are neither adequate nor appropriate to our specific case. They are generalities. And we must interpret them as such. Is it possible to get good returns by investing in the financial market? Yes, but a great wallet for Rita, 41 years old, mother of 2 children and businesswoman, may not be good for Pedro, 30 years old, without children and a doctor.

Our life story and humor

Our relationship with risk has a lot to do with our life story. Hence we associate risk with loss, even in relation to investments. We know that the time we were born, or the place where we live and work, the school where we study, the people we meet, decisively influence our success. In savings and investments as well. We only know the history of those who became millionaires with the financial markets, but we don't know those who lost a lot in the game of luck and risk.

Humor also has an influence. In fact, humor influences many of the decisions we make throughout our lives. About this we made a podcast where we analyzed Noise, a book by Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony and Cass Sunstein, where humor was recognized as a source of error. The same person, faced with the same situation, can make different decisions depending on their mood.

And in investments? We often attribute our bad mood to the evolution of equity indices on a given day. A recent study poses the question in reverse: Does mood influence market direction?

The study, by Alex Edmans, Adrian Fernandez-Perez, Alexandre Garel and Ivan Indriawan and designated by Music Sentiment and Stock Returns Around the World, concluded, with high robustness, that when people listen to happy music, the market performs better, that is, a pattern of upbeat music one day means higher stock prices the next.

Removing this effect caused only by emotions seems to be a real critical success factor. But not everyone will make it. In fact, perhaps no one can fully do this. Emotions are powerful and so is the pleasure taken from the game.

If we cannot be rational, we must be reasonable. It is difficult to have an attitude full of rationality, with rules and ways of acting for each situation, eliminating the noise and emotional and cognitive biases of each decision. Demanding too much of ourselves, raising expectations too much, can mean greater disillusionment and an unmeasured and unattainable ambition. We have to strike a balance that allows us to keep some emotion in what we do, but knowing the implications of those mistakes.

The disposition effect in the context of luck and risk

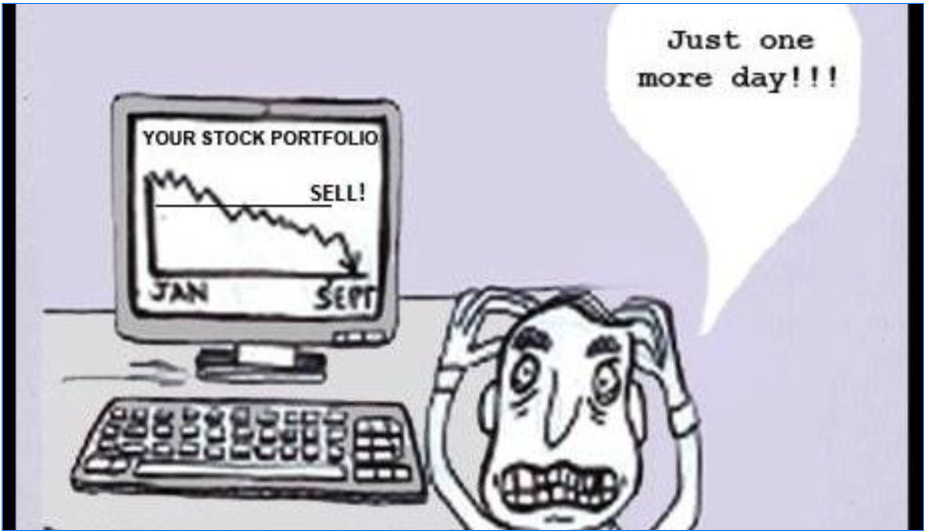

The disposition effect is one of those mistakes and is, in a way, related to luck and risk. Originally proposed by Shefrin and Statman (1985) based on the work developed by Kahneman and Tversky (1979), the disposition effect means that investors tend to sell investments that have gone up (gains) too early and hold for a long time those that have gone down. (losses), having as a reference the acquisition price or a price mentally defined by the investor. In a context of loss aversion, the disposition effect is an emotional bias in which investors are reluctant to take recent losses, thus showing themselves to be willing to accept risks that they do not normally take. This results in inefficiency and a gradual deterioration in value. They probably believed in luck when investing.

Note the typical case of a loss-averse investor who consults the position of his investments at a certain time of day. When seeing that some positions are losing, how will the investor react? The idea of a loss is so painful that the first reaction is to hold the position until the losses are eliminated. The investor is acting on emotions. In relation to positions that are gaining, the most natural thing is to sell to avoid additional risks.

Willingness to lose money

Deciding according to your emotions, causes irreversible damages.

Following certain instructions just because we are told to do so, even if those tasks/tips are ridiculous or dangerous, is an attitude related to cognitive shortcuts. It's why we think a superstar CEO is a great manager, or a financial advisor can always offer good investment advice, or even that market gurus always have something useful to tell us. It's hard to separate content from luck and the different types of people and roles they play. There are certainly good CEOs, good analysts and amazing gurus, but we can't believe they're all like that.

Although designed to ease our way in the world of investing, cognitive shortcuts are a disposition (inclination) to lose money. The danger of the attribution effect when applied to CEOs, analysts, investment gurus or forum with the latest tip, is that they are just as mentally limited as we are.

This gives rise to a great maxim: If we have to lose money in the markets, let it be with our own mistakes.

It is in less sophisticated investors that the disposition effect is most revealed.

Dhar and Zhu (2006) carried out an empirical study where they concluded that, in general, the investor's remuneration, wealth, profession and age (characteristics indicated for a more sophisticated investor) are associated with a lower presence of the disposition effect.

Investors must be able to recognize the existence and the great difficulty in combating the effect and, more specifically, the behaviors that explain it, associated with luck and risk. In the decision-making process, organization, rigor and investigation (research) are some of the ways to mitigate or overcome these and other behaviors.

Vítor is a CFA® charterholder, entrepreneur, music lover and with a dream of building a true investment and financial planning ecosystem at the service of families and organizations.

+351 939873441 (Vítor Mário Ribeiro, CFA)

+351 938438594 (Luís Silva)

Future Proof is an Appointed Representative of Banco Invest, S.A.. It is registered at CMVM.