Investment: top mistakes of an Investor

Why did we make so many wrong decisions about investing?

In order to be better investors, we must be aware of the mistakes and biases that we show throughout the investment process. We cannot dissociate our behavior from the evolution of the investment portfolio.

The main objective of this article is to awaken investors to the behavioral issue and explore in more detail the most common mistakes we make as investors.

BEHAVIORAL FINANCE

For some decades now, several authors and researchers have been dedicated to the study of behavioral economics, relating concepts from different areas such as psychology, sociology, neurology and economics. In 2017, the economics nobel was awarded to Richard H. Thaler precisely for his work developed in these themes. Thaler argues that understanding human nature can improve the explanatory power of economic theory and thus find better solutions to society's problems.

If the traditional approach to finance is based on assumptions about how investors and markets should behave, the behavioral approach seeks to explain the investor behaviors that are actually observed. Investors are faced with choices and “pushed” to a particular option for reasons of context and environment.

We also highlight the work developed by Daniel Kahneman (nobel prize in economics in 2002). Alone, or with his longtime colleague Amos Tversky, he has revealed over and over that he was fascinated with understanding why people are so strange, complicated and irrational in decision-making in a risky context.

The work of analyzing the investor's behavior and knowledge should focus on detecting the error or bias, on the assumption that the error exists and on how it can be overcome or mitigated.

Source: Morning Star

MAIN COGNITIVE ERRORS AND EMOTIONAL BIAS

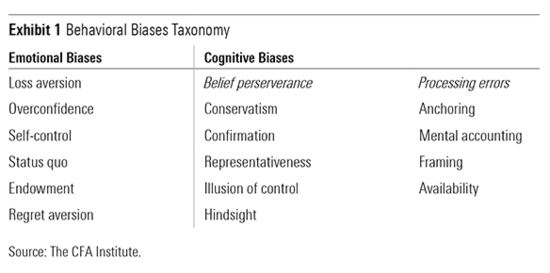

There are several errors and biases that we show when we are investing. These errors and biases can, in a simple way, be divided between cognitive errors and emotional biases.

Cognitive errors in investments are behavioral biases that result from wrong or imperfect reasoning. They are related to memory errors, information processing and statistical data. Emotional biases result from the influence exerted by feelings on the formulation of reasoning. They come from impulse and intuition.

Below we present some of these errors and biases and how to identify them.

COGNITIVE ERRORS IN INVESTMENT:

-

Conservatism: Too much weight on old information.

Here the investor reveals difficulty in incorporating new information and ideas and chooses to maintain a belief or position, ignoring new information because it is difficult to analyze and interpret. Reacts faster when Information is simpler (lower cognitive cost).

Conservatism can also be seen in constantly adjusting targets and estimates based on past information.

When new information is presented we should ask:

- How will this information change my predictions?

- What impact does it have on my estimates?

- Confirmation bias: Uses and analyzes different data and models just to support the vision and way of thinking.

The investor ignores and undervalues information and opinions that contradict their beliefs and considers only positive information about an investment while ignoring negative information about it.

We should look for different opinions and information that challenge our ideas, such as positive and negative information to increase the chance of making better decisions.

Some of the important questions to ask are:

- What information do you value most when analyzing investment opportunities? Return, risk, both, capital guarantee, term, issuer or others?

- Independently review an investment opportunity or use a third party? Who? Opinions from account manager, media or friends?

- Representativeness: Uses a small sample of information to draw a conclusion or decision to change the strategy.

The investor overreacts to new information, taking a view or position based solely on new information or small samples. It also has a tendency to extrapolate past performance into expected future returns.

To mitigate or eliminate this error, we must develop a long-term financial plan and investment strategy.

- Retrospective bias (inverted bias): Ability to look back and then try to delude our mind into thinking that if we had made a different decision the outcome would have been favorable.

It's uncomfortable to admit that we're wrong (it's an ego defense mechanism) and the memory isn't perfect. We fill memory lapses with what we prefer to believe. That's why it's important to evaluate and record investment decisions, both bad and good.

One idea taken from this error is the importance of not confusing added value with a market rally or luck.

- Illusion of control: A tendency to believe that one can have control or influence results when, in fact, one cannot.

People who can select their own numbers in a lottery are willing to pay a higher price per ticket than people who play on randomly assigned numbers. As a result of this illusion, people trade more than usual (traders believe they "have control").

Here, investors tend not to diversify their portfolios correctly (concentration on companies they believe they can control). It is advisable to view opposing views and it is critical to keep records of applications and operations.

- Anchoring and Adjustment Effect: We put too much emphasis on an anchor.

Past prices and market levels and reputation reveal little about the future potential of an investment. We use mental shortcuts to estimate probabilities of getting a result.

Some of the important questions to ask are:

- Am I holding this investment based on rational analysis, or am I trying to get a price that I'm anchored to, such as the purchase price or a price above the waterline?

- Am I making this market forecast based on rational analysis, or am I anchored to last year's market levels?

- Mental accounting: Concept related to the processing of financial transaction information.

We treat a given sum of money differently from another sum of equal amount. We do not consider a portfolio in an integrated way, but in categories, creating benchmarks as a self-monitoring mechanism. Do we consider capital and income gain separately rather than parts of the same total return? Do we ignore correlations between different assets?

We must focus on the integrated vision of heritage and total return.

- Framing prejudice: Related to how we structure or frame a question or answer.

Provide the same information in different ways: there is a 30% chance of passing or there is a 70% chance of failing.

The investor tends to lose sight of the big picture and focus only on one or two specific points. For example, we tend to focus on short-term market fluctuations, which can result in excessive trading.

Investors can become more risk averse if presented with a gain benchmark (we want to consolidate gains), but they can become more risk-loving if presented with a loss picture (we want to go after the loss).

Risk tolerance questionnaires and investment policy are increasingly important to alert investors to the effects of this cognitive error.

We should eliminate any reference to incurred gains or losses - focus on the future prospects of an investment. Focus on expected return and risk rather than profit and loss.

EMOTIONAL BIASES IN INVESTMENT:

- Loss aversion: Related to the disposition effect and the prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky).

We hate to lose. Psychologically losses are much more powerful than gains.

The disposition effect relates to the tendency of investors to sell assets that have increased in value (earnings), keeping assets that have lost value. In a context of loss aversion, the disposition effect is an emotional bias in which investors are willing to accept risks they normally do not take. This results in inefficiency and a gradual deterioration in value.

In fact, having more desire to sell positive investments (winners), the investor favors excessive trading. This trend causes an increase in the level of taxes and commissions.

We are risk averse when we experience a gain and we are risk averse when we experience a loss.

We must overcome our inability to recognize losses and accept more risk to increase gains, not mitigate losses.

- Overconfidence: Illusion of knowledge combined with self-attribution bias.

Over-reliance on certainty and predictions, combined with wrong reasoning and hope, underestimating risks, overestimating expected returns, holding poorly diversified portfolios, trading excessively, getting less return than the market are emotional biases. A kind of “Gut feeling and hope”.

Hence the famous phrase: Don't confuse brains with a bull market. Some of the important questions to ask are:

- Do you believe, have faith, in your intuition, opinions and cognitive abilities?

Was the good performance lucky because the market rose or was it based on good decisions and rigorous fundamental analysis?

- Self-control: Related to the savings and consumption model.

Loss of self-control means that we spend too much now, because it feels good, and we don't save enough for the future. We've completely failed to pursue our long-term goals because of a lack of self-discipline.

Investors must have an investment plan and a household budget and an asset allocation strategy appropriate to long-term financial goals – failing to plan is planning to fail.

If savings are insufficient, investors tend to accept more risk in the portfolio in an attempt to increase returns.

Some of the most important questions to ask:

- What percentage of disposable income do you save annually?

- Do you tend to select investments with regular distribution of income?

- Do you need that savings income to meet your current expenses (to maintain your standard of living)?

- Possession or endowment effect (Endowment bias): Related to the origin of the heritage, ie, inherited heritage is very difficult to sell for emotional reasons.

Too much weight on investment familiarity. This situation leads to inappropriate asset allocations taking into account risk tolerance levels and long-term financial objectives.

Therefore, the investor should compare inherited (family) investments with a diversified portfolio or a benchmark.

An important question to determine the weight of this effect is:

- If a sum equivalent to the inherited assets had been received in cash in which assets would you invest?

- Aversion to regret: Related to something we did or didn't do in the past that is influencing our thinking today.

Investors tend to avoid making decisions for fear that the decision will be wrong. So there is a tendency to select investments we are familiar with or to "follow the herd".

Education is paramount, as investing too conservatively or too risky can mean that long-term financial goals will not be achieved.

Examples of questions we should ask:

- Do you show a more conservative attitude because some investments in the past went wrong?

- Do you feel safer in popular investments that avoid the feeling of guilt and personal responsibility for them?

- Status Quo: It means doing nothing (not to be confused with conservatism) despite possible new information.

Here the investor fails to explore new investment opportunities. It's more comfortable to keep everything as it is despite the fact that the portfolio is often unsuitable for current circumstances.

It seems symptomatic that we need a bait or a push to act, that we make anecdotal mistakes, and that, yes, it's true, there are no free lunches.

Richard H. Thaler predicts that “in the not-too-distant future, the term 'behavioral finance' will rightly be seen as a redundant phrase. What other type of finance is there?” In other words, finances are behavioral and there is no finance without errors and biases.

Just as we know our physical limitations, we know what we are and are not capable of doing, we also need to recognize our mistakes and cognitive and emotional biases. If we do, we will be in a much better position to make decisions and be better investors.

Vítor is a CFA® charterholder, entrepreneur, music lover and with a dream of building a true investment and financial planning ecosystem at the service of families and organizations.

+351 939873441 (Vítor Mário Ribeiro, CFA)

+351 938438594 (Luís Silva)

Future Proof is an Appointed Representative of Banco Invest, S.A.. It is registered at CMVM.